helicopter pilot whose foot was ….

helicopter pilot whose foot was obliterated by a bullet that penetrated his aircraft. Some had lost vital organs, suffered permanent nerve damage or were scarred.

“I’d better quit feeling sorry for myself,” Norlander told himself. “Maybe it takes me a bit longer, but I’ve got two legs.” After treatment at Camp Zama, he was strapped to a stretcher and carried onto a fixed-wing aircraft, where he rode over 10 hours to Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California. From there he was loaded into an ambulance, on his way to Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco, where he remained for several months.

After recovering, Norlander questioned the war that had defined his early adulthood—a conflict between communist powers and the anti-communist West. Despite America’s overwhelming firepower, he came to see the Viet Cong as “a worthy adversary.”

He recalled offering a Vietnamese translator a carton of cigarettes, only to have the man ask for soap instead. A small cut, once marinated in the heat and grime of the jungle, could become a festering wound. As a U.S. soldier, Norlander could have these wounds doused in hydrogen peroxide and pumped with penicillin—but health services in rural areas of Vietnam were largely underdeveloped.

“In the U.S., freedom of the press, freedom to vote for the candidate of your choice, freedom to criticize the government, that’s ingrained in us,” he said. “Once we pulled out, once Saigon fell, once there was no more bombing, what those people were really interested in was food and medical supplies.”

Back home, America’s attitude toward the war had soured. Protests peaked in 1969 and became confrontational in 1971, when a large May Day protest led to 12,000 arrests, according to a book by Lawrence Roberts that cataloged the event. Reasons for opposition were multifold—civilian casualties, government misinformation about the war, and atrocities like the My Lai Massacre, among others.

The veterans of the Vietnam War received no revelry from the public. Many carried survivor’s guilt, others the weight of moral ambiguity, including orders to distinguish enemies from civilians in a war where such lines were often invisible. Norlander would grapple with these ambiguities for decades.

When he left the hospital, he was relieved to learn of his next assignment: the First Infantry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas.

“Nobody’s going to be shooting at me? That sounded great,” he said. As a tank driver, he found the work “easier than driving a stick-shift Volkswagen.”

Eventually, Norlander was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army. His daughter, Lori, was three months old when he returned from Vietnam, and he’d had his fair share of artillery and explosives.

He and his wife, Judy, had a son, Jared, in 1977. They moved around, eventually returning to California, where Norlander worked at a uniform rental company for two decades.

In 2010, after “retiring,” he took one more post—as a parttime GRF Security officer at the Main Gate in Leisure World, working the night shift and directing traffic. By 2019, he’d moved his way up to secondin- command: GRF Security Department manager, a position in which he still serves today.

A lifetime removed from the jungles of Vietnam, Norlander still carries the quiet strength of a soldier who fought his way home.

Today, he dedicates his days to serving the people of Leisure World. The official motto of the U.S. Army still applies: “This We’ll Defend.”

A small cut, once marinated in the heat and grime of the jungle, could become a festering wound.

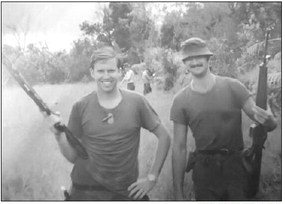

Larry Norlander and Sgt. Cliff Smentek pose with M16 rifles in Vietnam.

Image Courtesy Larry Norlander