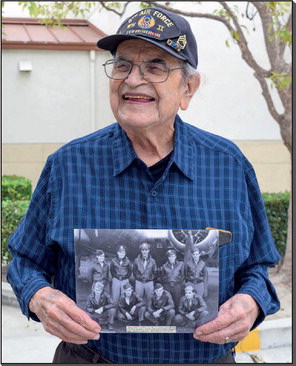

WWII survivor just turned 102

HONORING LW VETERANS

He survived a Christmas Eve crash and rendered aid to his seriously wounded crewmates. By war’s end, he was awarded an Air Medal with Four Oak Leaf Clusters.

The LW Weekly salutes the men and women of the Armed Forces who serve and have served in all branches of the U.S. military. Their sacrifice will never be forgotten and is the foundation of today’s freedom and democracy the world over. Alfred Arrieta, who has lived in Leisure World for nearly 30 years, exemplifies the spirit of wartime veterans who served with distinction. This story, which ran in 2022, has been updated and is being reprinted in honor of his 102nd birthday on May 23.

by Ruth Osborn

Communications Director

Alfred G. Arrieta, a 28-year resident of Mutual 12, was barely out of high school when he was drafted into the U.S. Army Air Corps as World War II raged in 1943. Nothing in peacetime life prepared the young American, only 19 years old, for the violence that lay ahead. But like many men of his era, he responded, trained hard and fought a furious fight to preserve the fundamental freedoms that define life in a free, democratic society.

Eleven months before the Japanese Empire launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt gave a speech that described a world where everyone could enjoy four “essential human freedoms,” freedom of speech, freedom to worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear.

By the end of the war in 1945, 50 million men between 18 and 45 had registered for the draft, and 10 million had been inducted in the U.S. military, according to wikipedia.com.

Alfred Arrieta, born and raised in El Paso, Texas, was one of them. Before it was all over, he completed 32 missions over enemy-occupied Europe as a waist gunner in a B-17 bomber. In mission No. 29, he survived a Christmas Eve crash and rendered aid to his seriously wounded crewmates. By war’s end, he was awarded an Air Medal with Four Oak Leaf Clusters.

The real reward was that he survived. The average crewman had only a one in four chance of actually completing his tour of duty, according to www.eyewitnesshistory. com.

And he went on to marry twice, raise 10 children, owned a TV and VCR repair shop in Norwalk, and continues to live a life of purpose in Leisure World with his wife, Frances. He still enjoys tooling around LW in his golf cart.

Even through the veil of years, his war experience remains in sharp relief. War quickly takes the measure of a man, and even at his young age, Arrieta found that he measured up.

“We were all young,” he said. “You just take it in stride. We had the best training of anyone.”

Arrieta did well on aptitude tests. After basic training, he was assigned to a radio operator/ mechanic school in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “I was never so cold in my life,” he said, but he learned a lot.

He warmed up in his next duty assignment, the Army Air Force Flexible Gunnery School at Kingman, Arizona. Activated Aug. 4, 1942, Kingman Army Air Field was built on more than 4,000 acres in three months and existed for just over three years.

In that short period, Arrieta and 36,000 other gunners were trained to crew the B-17. He started work in the classroom, studying orientation, safety, gun installation, aircraft recognition, turret training and tactics. He also learned aerial gunnery, aircraft recognition and how to field strip and reassemble a .50-caliber machine gun while blindfolded and wearing gloves.

Next stop was Dyersburg Army Air Base in Tennessee, the largest combat aircrew training school in the U.S. and the only B-17 training base east of the Mississippi River. There Arrieta practiced air-to-ground and air-to-air weaponry, plus night flying in the B-17 cockpits. Dubbed the “Flying Fortress,” the first mass-produced model carried nine machine guns and a 4,000-pound bomb load, according to wikipedia.com. About 7,700 crewmen received final training in Dyersburg before heading into the war zone. He then joined a crew to transport a new B-17 to RAF Prestwick, located near Glasgow, Scotland. From there he took a slow ship to Liverpool. It was August 1944.

The Allies would launch a second invasion from the Mediterranean Sea of southern France on Aug. 15, and the liberation of Paris followed on Aug. 25.

As the waist gunner of the nine-man B-17 bomber crew, Arrieta was good at his job. He praised lead pilot Capt. Donato Yannitelli, Jr. as being super smart and steady as a stone. As lead pilot, Yannitelli was at the higherrisk apex of attack formations that consisted of hundreds, even thousands, of planes.

Arrieta’s first missions were bombing Nazi-occupied regions in France. They were short runs, three or four hours at most.

As the Free French (military and quasi-military organizations operating with other Allied nations) gained control of the area, the B-17s of the 92nd Bomb Group were rerouted to targets in Germany. These were long-haul raids, up to 12 hours total.

The planes were unheated and open to the outside air. The crew wore electrically heated suits and heavy gloves that provided some protection against temperatures that could dip to 60 degrees below zero. Once above 10,000 feet, Arrieta donned an oxygen mask. Nearing the target, each crew member would put on a 30-pound flak suit and steel helmet designed to protect against antiaircraft fire.

These missions penetrated deep into enemy territory. For hours, the men anxiously scanned the skies for attacks by fighters armed with machine guns, cannons or rockets.

It was Christmas Eve 1944, Mission No. 29. The Eighth Air Force launched 2,046 bombers and 1,000 fighter escorts to attack German airfields, fuel depots and communication centers.

Arrieta’s 92nd Bomb Group would be flying in broad daylight at an altitude below 10,000 feet, no cover at all.

“For the Germans, it would be like shooting clay pigeons,” said Arrieta. “We knew we would probably be shot down.”

He was 21 years old. The Battle of the Bulge was raging in the densely forested Ardennes region between Belgium and Luxembourg. Arrieta was aboard the brightly colored lead-ship piloted by Yannitelli, who directed the bombers to pre-determined points where they would organize themselves into attack formations.

Arrieta was braced on the curved floor of the fuselage, while standing in front of an open window in a 200-mph slip stream in temperatures below zero.

He recalls: “The Germans had overrun our troops in the Ardennes Forest, and we bombed and strafed German troops in support of our foot soldiers. We dropped our bomb load and barely made it inside the border. Our plane was all shot up.” And so were they. Top turret gunner Stanley Bellman from Minnesota was unconscious with an eye out of its socket. Arrieta, who was the medic, gave him morphine, pushed his eye back in and bandaged it up, as the plane plummeted to earth: “You’re young, you do what you have to do. They train you for that.”

None of the crew had parachutes to bail out as they, and the guns, had been jettisoned to make the plane lighter. The crew got into crash-land position, as pilot Yannitelli, who was also wounded, bellylanded the plane on a French farm field. A total of five were wounded, and “four of us lucky ones were OK,” Arrieta said. “We were picked up by Free French fighters and taken to an American hospital in Lille, France.”

Each man had a sealed escape kit. When Arrieta opened it up, he found the usual supplies—K-rations, water, chocolate, matches, medical equipment, etc.—and 5,000 francs. So he and crewmates got a hotel room in Lille and spent the best Christmas of his life.

“We were so lucky to be alive. A taxi driver took us to a place where there was beer and dancing,” Arrieta said. “It had little lights everywhere and was packed with people. Everybody was so happy. We thought that the end of the war was near.”

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, ended up being the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front. Between Dec. 16, 1944, and Jan. 16, 1945, the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces shot down more than 400 enemy fighters and destroyed 11,378 German transport vehicles, 1,161 tanks, 6,266 railroad cars and 36 bridges, according to www.britannica. com. The Allies of World War II formally accepted Germany’s unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Eastern Front.

Arrieta went on to live a full life. His legacy includes 10 children, 17 grandchildren and eight great grandchildren.

“My days are really not long enough. My children are doing well, and I’m busy,” he said “I’m a fortunate man.”

Alfred G. Arrieta in 1944